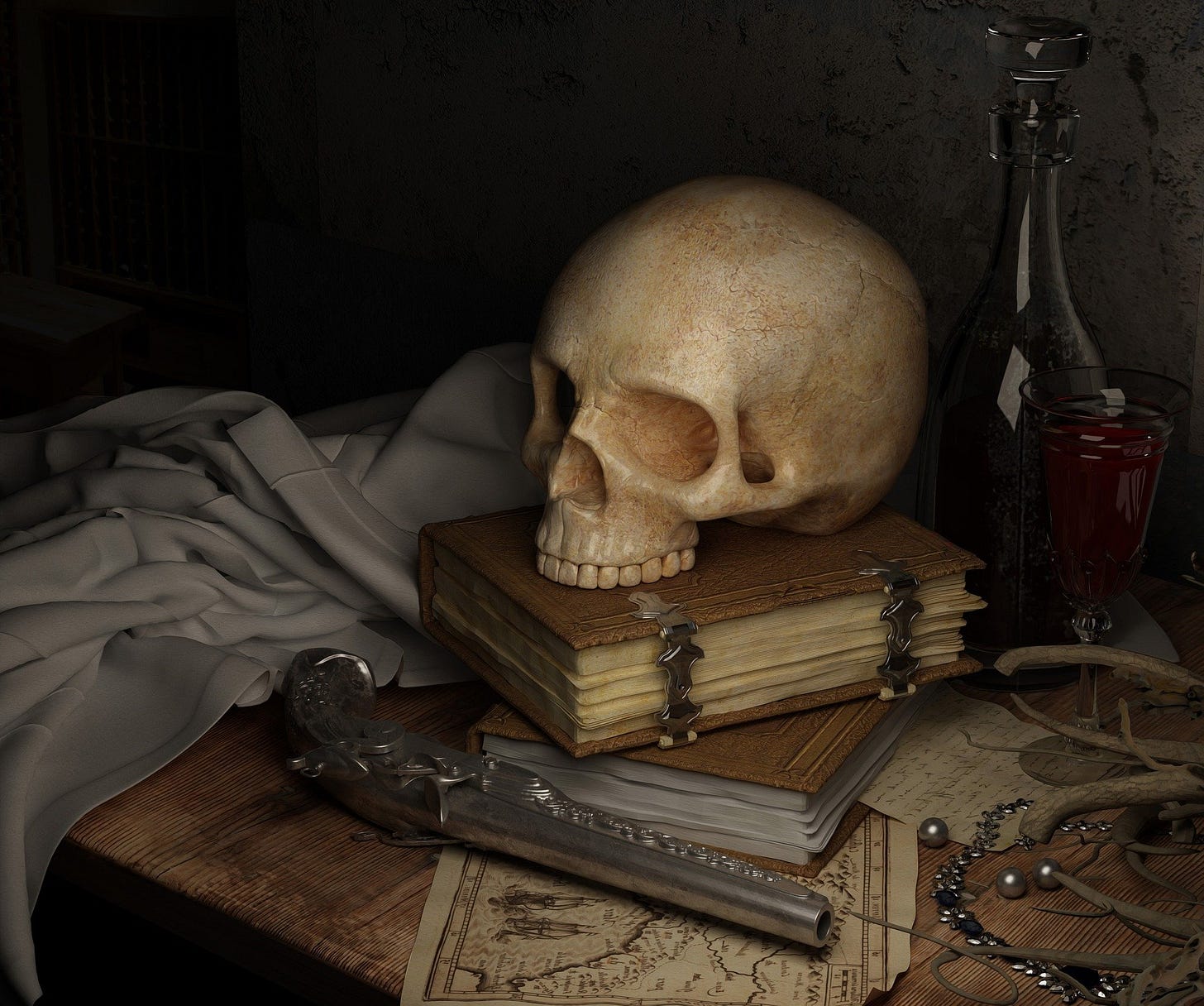

The Mouths of the Best Poets: A Few Notes On Mortality, Compassion and Wisdom

“The mouths of the best poets,” Mark Heard sang, “speak but a few words, then lay down stone-cold in forgotten fields.” If even Shakespeare, Longfellow and Galway Kinell pass into the dark, how much more quickly will we, the mundane, be forgotten?

To illustrate this point, I once asked a classroom full of students to raise their hands if they knew their fathers’ names. All hands went up. I then asked them to raise their hands if they knew their grandfathers’ names. Nearly the same number of hands went into the air. When I asked how many knew their great-grandfathers’ names, few hands were raised. When I finally asked how many knew their great-great-grandfathers’ names, not a single hand was raised.

I pointed out that according to the results of this experiment, none of our names would be remembered, even by our direct descendants, in four short generations. My students were unfazed. News of their mortality and impermanence failed to impress them.

That’s how it is when we are young. Most of us just don’t think seriously about the fact that we will die. If we do, death is remote, an abstract tragedy that befalls old people and the occasional unfortunate stranger.

The illusion we carry when we are young that life will go on forever leaves us with no sense of scale. Without a conviction that everything is coming to an end, it’s hard to tell what really matters. We can’t focus on what will outlive us when we believe we will live forever.

This is one reason young people tend to freak out. To the young, everything seems permanent. Every disappointment, every grievance, every loss seems everlasting. Every conflict, every tempest of the heart seems worthy of historical note.

Increased perspective is one compensation for aging. The approaching end tends to make things clear. Suddenly, wasting time on petty slights and shallow entertainments seems foolish. We regret the wasted time.

Mercy and compassion become easier too because we see how little comes from holding grudges. We don’t fret about every problem because we know that sooner or later we simply won’t be around to endure them. Instead of wasting our energy trying to resolve every unfortunate circumstance we learn to look for the places where the investment of our remaining strength and energy might do the most good and forget the rest. The perspectives we can develop as we age are aspects of wisdom.

Few of us, however, end our days wise. Wisdom requires confronting the bad news of our mortality. Most people put this confrontation off as long as possible. Our society’s worship of youth and our culture of endless distraction encourage denying our mortality until it becomes undeniable. Death, the one fact about life of which we can all be absolutely certain, therefore still comes as a surprise to many.

A society that repudiates mortality repudiates wisdom. In its fervent attempt to deny our mortality, our society denies most of us of the joys of maturity. Rather than free us to experience full adulthood, it condemns us forever to be only old children.